This is an html-rendered Jupyter notebook. If you want to do the exercises right here, open it in Colab or download and edit it locally. In former case, you need to complete a little quest and install CUDA and PyCuda, its Python binding. On a Debian-based machine, this will probably be enough: * apt-get install nvidia-cuda-dev nvidia-cuda-toolkit * pip install pycuda

Prerequisites: basic knowledge of Python and C, basic algorithms, and generally how computers work.

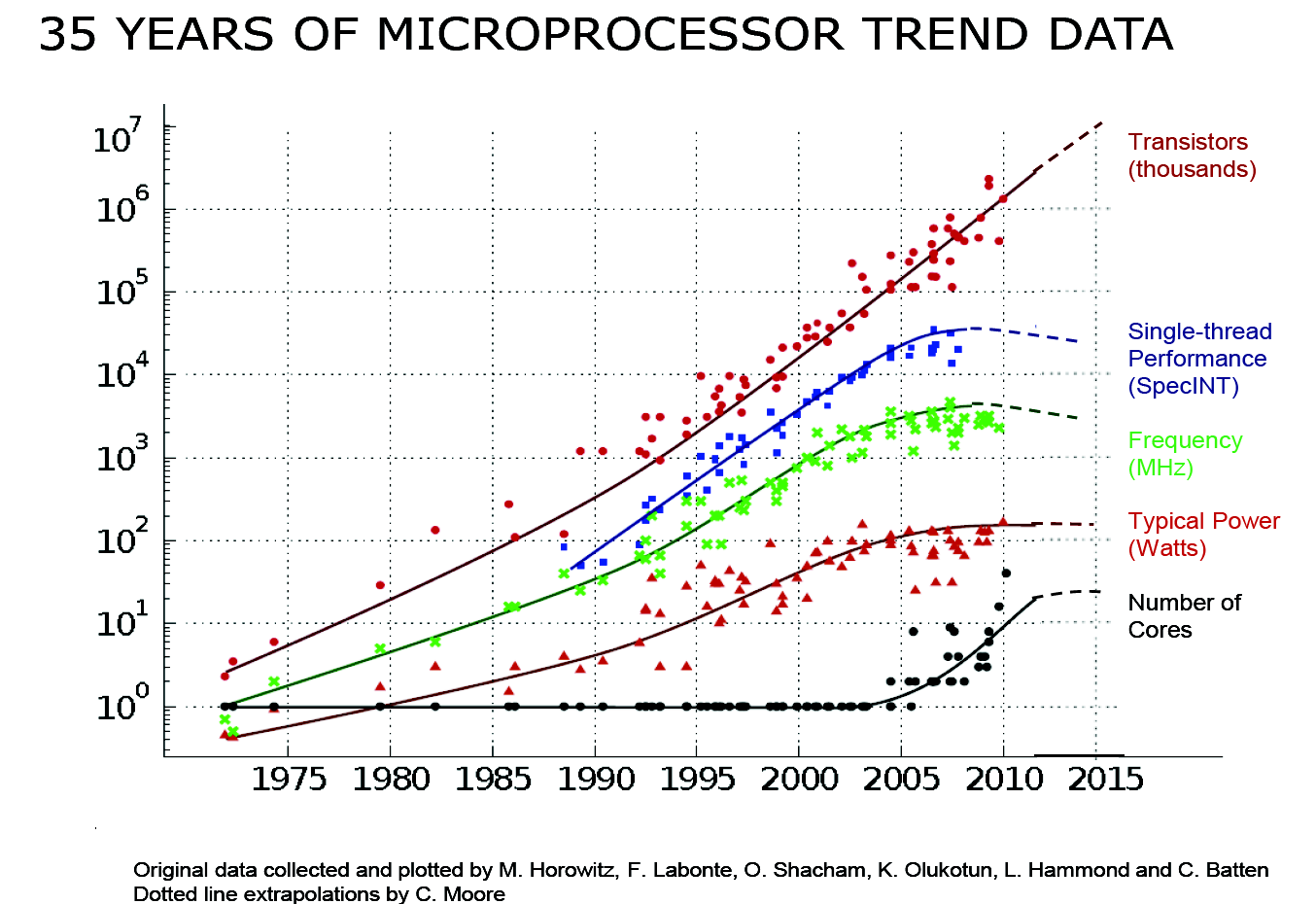

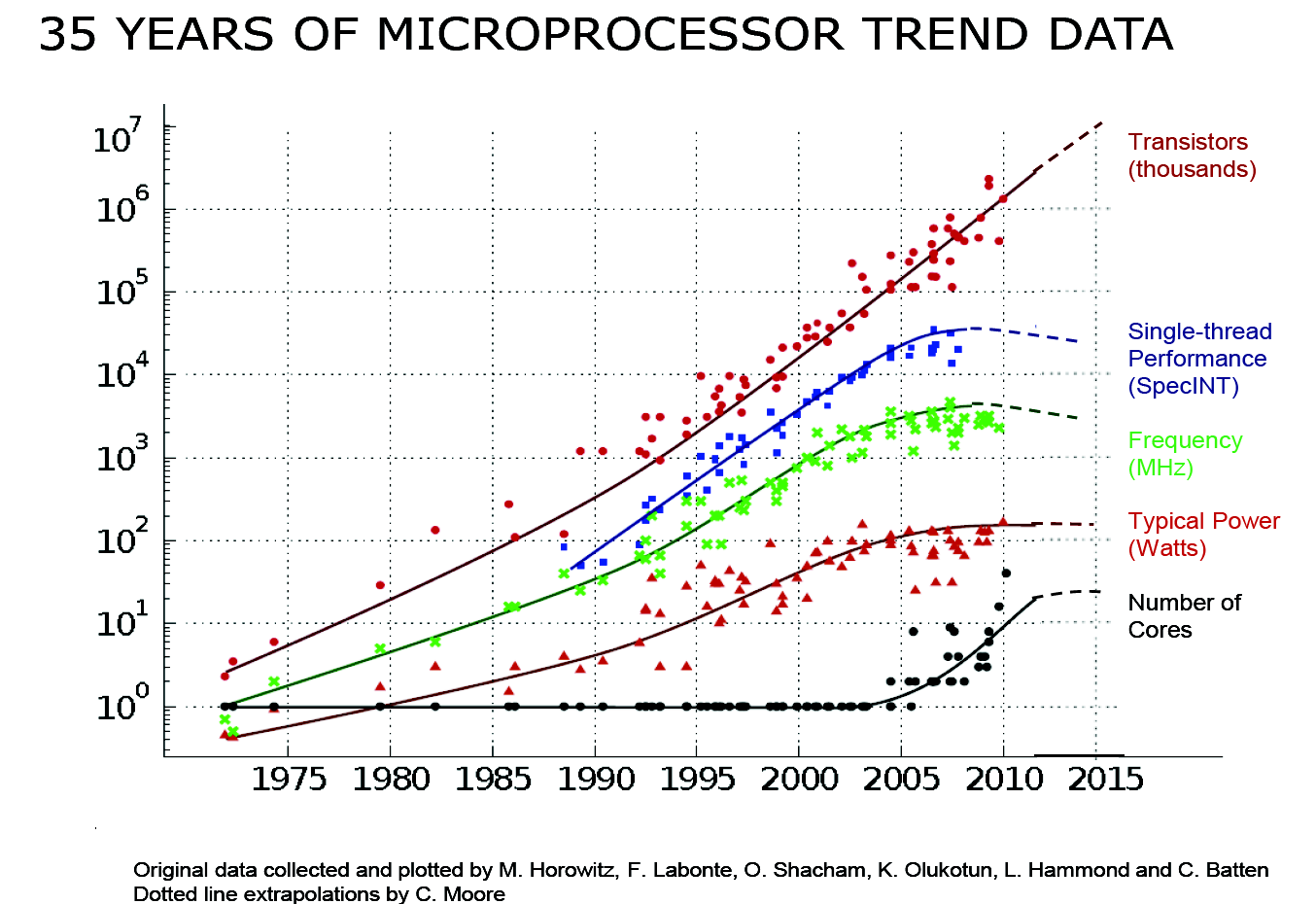

Here is a graph that roughly represents what is happening in the CPU world:

Moore’s law is the observation that the number of transistors in a microprocessor doubles about every two years. This roughly means that the performance doubles too.

You can see that around 2005 there became a shift in design .

The cores are more or less independent.

Modern GPUs appeared in early 2000s. They exploit the specific area they operate.

There are physical limitations to the speed of a core.

One solid one: the speed of light. You at least need the time for electromagnetic wave (this is light too) to pass from one side of the motherboard to another.

Some of them have

The default free GPUs available on Google Colab are rather powerfull. Author has no idea why Google does this, but this is awesome.

Clock frequencies — for example, Intel Core i7 can have. This gives an upper bound

There are two types of

There was a period in time when hedge funds hired computer graphics guys from game companies because of their computing skills.

There are several.

This is like with Windows and Linux.

We will stick with CUDA, because it more spread, especially in fields where noone cares, like deep learning.

CUDA programming involves running code on two different platforms concurrently: a host system with one or more CPUs and one or more GPUs.

Threads on a CPU are generally heavyweight entities. The operating system must swap threads on and off CPU execution channels to provide multithreading capability. Context switches are therefore slow and expensive.

By comparison, threads on GPUs are extremely lightweight. In a typical system, thousands of threads are queued up for work — in warps of 32 threads each. If the GPU must wait on one warp of threads, it simply begins executing work on another. Because separate registers are allocated to all active threads, no swapping of registers or other state need occur when switching among GPU threads. Resources stay allocated to each thread until it completes its execution.

In short, CPU cores are designed to minimize latency for one or two threads at a time each, whereas GPUs are designed to handle a large number of concurrent, lightweight threads in order to maximize throughput.

The host system and the device each have their own distinct attached physical memories. As the host and device memories are separated by the PCI Express (PCIe) bus, items in the host memory must occasionally be communicated across the bus to the device memory or vice versa as described in What Runs on a CUDA-Enabled Device?

You can easily dump 98% of performance of you think this way.

CUDA is available for many languages.

Nice documentation can be found here: https://documen.tician.de/pycuda/index.html

If you are on Colab, go to Runtime -> Change runtime type -> Hardware accelerator and set it to “GPU”.

# you may want to clear the output of this cell after installation

from IPython.display import clear_output

# this might take a while

!pip install pycuda

clear_output()import numpy as np

from pycuda.compiler import SourceModule

import pycuda.driver as drv

import pycuda.autoinitLet’s start with a simple example and then dive deeper.

Just like C or C++, except that you use some custom built-in functions and specifiers.

CUDA is pretty much like normal C, except that you can specify some functions to be run as. Depending on implementation, the workflow goes as follows:

You need to think of your computer as a heterogenious machine: there is host data and device data.

In fact, kernel runs are concurrent — you program does not block until kernel run is complete. Newer devices can even run multiple kernels concurrently this way and wait for their results.

For testing and coordination with host, we will use NumPy package. If you don’t have it, install it: pip install numpy.

NumPy is a package for linear algebra and array manupulation in Python. It is written in C and is very efficient, but runs solely on CPU, so we will benchmark against it.

# lets generate our test data: two float arrays filled with something random

a = numpy.random.randn(100).astype('float32')

b = numpy.random.randn(100).astype('float32')

# the type needs to be specified in this case, because randn's default type is float64, but CUDA knows nothing about it

# we need to create space where kernel should write its answers to

dest = numpy.zeros_like(a)

# this is the kernel itself

mod = SourceModule("""

__global__ void add(float *dest, float *a, float *b) {

const int i = threadIdx.x;

dest[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

""")

# you need to specify the source code, and PyCUDA will compile it

add_kernel = mod.get_function("add")

add_kernel(

drv.Out(dest), # specifies that this memory should be accessible for writing

drv.In(a), # specifies this should be accessible for reading

drv.In(b),

block=(100,1,1) # we'll talk about it in a minute

)

assert np.allclose(dest, a + b), 'WA' # checks that these are equal

print('OK') File "<ipython-input-27-afc857479fe4>", line 19

%%time

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxIn CUDA C API, you need to allocate memory explicitly. So this is actually really nice.

There is also drv.InOut function, which makes it available for both reading and writing, but we won’t use it in this tutorial because we need to test our code too.

Most of the operations here are memory operations, so measuring performance here is useless. Don’t worry, we will get to more complex examples soon enough.

GPUs have very specific operations. However, in case of NVIDIA GPUs managing it is quite simple: the cards have compute capabilities (1.0, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.0, etc.) and all features added at capability

You can check differences in this Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CUDA#Version_features_and_specifications

Reduction is any array-wise operation.

Assume the following problem:

Consider the following recurrence:

## Problem: dynamic programmingWe actually think about both work and step complexity now.

Some tasks, especially in cryptography, cannot be parallelized. But some can.

Assume we want to perform some associative (i. e.

Normally, we would do that with a simple loop:

float s = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

s += a[i];

}Its computation graphs looks like this:

This is optimal in terms of work complexity, but not in terms of step complexity: it’s

Let’s try this divide-and-conquer approach:

Now it’s still

When you unroll the recursion from top to bottom, you will see that to get each required value,

a = numpy.random.randn(2048).astype('float32')

mod = SourceModule("""

__global__ void sum(float *dest, float *a, float *b) {

const int i = threadIdx.x;

// for l from 0 to logn:

// __sync_threads()

// if the thread is active

// sum two elements into where they belong

// a[0] should containt the needed sum

}

""")

sum_kernel = mod.get_function("sum")

add_kernel(

drv.InOut(a),

block=(1024,1,1)

)

assert np.allclose(dest, a + b), 'WA' # checks that these are equal

print('OK')Threads are bandled in groups of 32. All threads in a group must be either waiting or performing the same operation. This is caused by architectural difficulties.

You can actually do the same stuff with 2d and 3d indexing — weird, right?

Now, things get harder. It’s time to tell how exactly GPU parallelism works.

Let’s get to our first example where using GPUs actually makes sense: matrix multiplication.

Our last (and hardest task) is to implement sorting.

You might notice that we advocated divide-and-conquer approaches most of the time.

It’s true. They work. But we can’t get an algorithm that works already.

# we'll use a deep learning library for benchmarking because I'm not familiar with anything else

import torch

a = torch.randn(10**8)

b = a.cuda()# this should run for ~15 secs

%time c = torch.sort(a)

%time c = torch.sort(b)CPU times: user 15.2 s, sys: 177 µs, total: 15.2 s

Wall time: 15.2 s

CPU times: user 274 ms, sys: 237 ms, total: 511 ms

Wall time: 511 msSo, 30 times speedup. So, we now what we need to compete against.

b.sort()(tensor([-5.4567, -5.3551, -5.3288, ..., 5.3529, 5.4484, 5.4486],

device='cuda:0'),

tensor([55083205, 8383169, 73705953, ..., 79814161, 50474932, 27805828],

device='cuda:0'))There are two types of sorting algorithms: data-driven.

The second can be represented and analuzed with sorting networks. Here is the one that we’ll use, it’s called bitonic sort.

It has

It is actually not that hard to implement. To make it clear, here is a slow recursive Python implementation:

def bitonic_sort(a, up=False):

if len(a) <= 1:

return a

else:

l = bitonic_sort(x[:len(a) // 2], True)

r = bitonic_sort(x[len(a) // 2:], False)

return bitonic_merge(first + second, up)

def bitonic_merge(a, up):

# assume input a is bitonic, and sorted list is returned

if len(a) == 1:

return a

else:

bitonic_compare(a, up)

l = bitonic_merge(a[:len(a) // 2], up)

r = bitonic_merge(a[len(a) // 2:], up)

return l + r

def bitonic_compare(a, up):

dist = len(a) // 2

for i in range(dist):

if (a[i] > a[i + dist]) == up:

a[i], a[i + dist] = a[i + dist], x[i] # this is how swap is done in Pythonbitonic_sort([57, 179, 42, 17, 300, 111])[300, 179, 111, 57, 42, 17]a = np.random.randn(10**8).astype('float32')---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-27-58a927c14aae> in <module>()

----> 1 a = np.random.randn(10**8).astype('float32')

NameError: name 'np' is not definedMost of it still applicable.

Again, GPU programming is very specific.

SSE and tensor cores.

Just like C or C++, except that you use some custom built-in functions and specifiers.

CUDA is pretty much like normal C, except that you can specify some functions to be run as. Depending on implementation, the workflow goes as follows:

You need to think of your computer as a heterogenious machine: there is host data and device data.

In fact, kernel runs are concurrent — you program does not block until kernel run is complete. Newer devices can even run multiple kernels concurrently this way and wait for their results.

What you need to understand about GPUs is that they are extremely specialised for their applications.

Intrinsics for that.

Now, a lot of value comes from cryptocurrency and deep learning. The latter relies on two specific operations: matrix multiplications for linear layers and convolutions for convolutional layers used in computer vision.

First, they introduced “multiply-accumulate” operation (e. g. x += y * z) per 1 GPU clock cycle.

Google uses Tensor Processing Units. Nobody really knows how they work (proprietary hardware that they rent, not sell).

Each tensor core perform operations on small matrices with size 4x4. Each tensor core can perform 1 matrix multiply-accumulate operation per 1 GPU clock. It multiplies two fp16 matrices 4x4 and adds the multiplication product fp32 matrix (size: 4x4) to accumulator (that is also fp32 4x4 matrix).

This is a lot of work per

Well, you don’t really need anything more precise than that for deep learning anyway.

It is called mixed precision because input matrices are fp16 but multiplication result and accumulator are fp32 matrices.

Probably, the proper name would be “4x4 matrix cores”, however NVIDIA marketing team decided to use “tensor cores”.

So, see, this is not exactly fair comparison.

down to int4 (16-valued, you heard correct)

You need to know a lot of this specialised stuff to write efficient code. So this is a bad idea to write libraries from scratch.

Anyway, for pedagogical and recreational reasons, today we will reinvent the wheel and do a matrix multiply.

It seems to be simple: you just need to .

What actually happens when you do s += x? This is not a single operation. Actually, four things happen:

Two threads may execute it in an interleaved fashion. Say thread A could get

Note: Atomics to do that

for small data types they are implemented on the hardware level and much more faster than that.

std::atomic is introduced to handle atomic operations in multi-thread context. In multi-thread environment, when two threads operating on the same variable, you must be extra careful to avoid race conditions.

If all the various types of device memory were to race, here’s how the race would turn out:

Register size (= machine word width) is 32 bits, but they also contain 64bit capability (otherwise having more than 4gb of memory would not be possible).

What you need to care for now is register

For now, you need to care about differe

Accessing global memory takes hundreds.

A lot of these are actually sparse. You can do stuff with social network graphs or web graphs.

Cool. But let’s disapploint us for a bit: